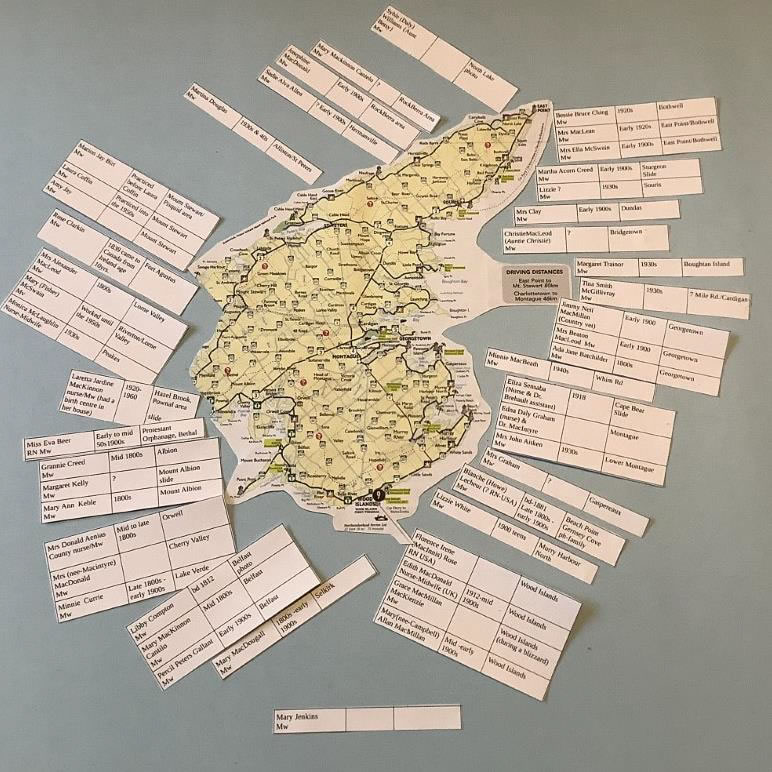

History of midwifery and midwives in PEI

The names of midwives, where and when they practiced, and their stories were gathered by Reginald "Dutch" Thompson, the presenter of The Bygone Days program on CBC. In an effort to honour PEI's midwives, Dutch kindly shared this history with the PEIMA.

There have always been midwives helping women during pregnancy and birth in PEI. Initially those midwives were among the Indigenous people, the Mi'maq, who lived here for thousands of years. When Europeans began searching for a route to the "Far East" they ran into the great open spaces in what is now Canada. They eventually brought women along with explorers and adventurers each with their own language, culture and religion thus growing a population of pioneers who survived by "helping out" each other. It is also recorded that in Upper Canada the Indigenous people "helped out" those pioneers and sometimes shared their traditions.

Various terms were used for the women that "helped out" other women during birthing, the act of delivery, and the places where it happened. Besides midwife, the terms used were gone birthing, aunty, gone catting. In the Island's Acadian villages midwives were called granny women. The French term for midwife, used in Quebec, is sage-femme — wise woman.

Midwives were often neighbours, grandmothers, mothers and sisters. There is a mention of a male midwife—a veterinarian in Wood Islands who was called in during a blizzard to help when the local midwifes were unable to get to location.

The records of midwives in PEI go back to the mid 1800s. Islanders may recognize a relative among them. They "helped out" well into the 1950s and 60s. Many doctors relied on midwives to care for their patients and would contact them if they perceived a problem they could not manage themselves. But doctors were few and far between in those days.

By the 1930s Depression, nurses returning home to PEI often took on the midwifery role. A few trained nurse/midwives who came to Canada as war brides also practiced here.

In those days, midwives did not charge for their services even though some stayed in the clients' homes to "help out" for a week or more leaving their own families to manage on their own. They often worked in pairs, learning from each other and relieving one another if the labour and postpartum care were long.

Prince Edward Island stories of midwives, the babies they helped deliver, and other folk who "helped out"

Jane Harris Fraser was born in the Cape Bear lighthouse in 1912, the year the Titanic sank. Her grandfather ran the Cape Bear lighthouse. Jane's uncle Thomas Bartlett ran the Marconi Wireless Station beside the lighthouse. It was he who first heard the Titanic's SOS signal when it hit the iceberg off Newfoundland.

Mrs. John Aitken was the midwife in Lower Montague in the 1930s. The doctor used to come across on the ferry from Georgetown and often couldn't make it in bad weather leaving the midwife to manage alone. There were fourty-four midwives on record in Queens County from 1800s to mid 1900s.

Ambrose Monaghan was born in Kelly's Cross in 1913. His mother was Lizzie Hugh. One of seven sisters, she was a midwife with eleven children of her own. Lizzie was Dr. Nelson Bovyer's go-to assistant when there was a difficult birth. On really cold winter nights, one of her sisters would heat old family heralds in the oven and put them under her clothes to keep her warm and to break the wind as she traveled to a labouring woman. Ambrose said you couldn't keep her home even during bad weather.

Elton Woodside from Clinton is another unsung hero of PEI. He operated the first air ambulance, and perhaps the only one PEI has ever had. In 1949, he landed on the ice in French River. He built his own plane and received his flying license in 1944. Elton was overing the Island like the dew—he also dropped the bundles of newspapers in villages across the Island.

Joyce Paynter moved to PEI as a war bride in 1946. Her husband was a farmer and the lighthouse keeper of the Cape Tryon lighthouse. She was an English-trained nurse/midwife. When Joyce went into premature labour with her second pregnancy during a raging blizzard her husband went by horse and sleigh for Elizabeth "Peach" Duggan, a neighbour and friend for help. Peach was also a registered nurse and midwife. Peach arrived across the fields with her flannelette pajamas under her cloths to keep her warm. Another sled went to Kensington for a doctor. The Flying Farmer Elton Woodside brought out Dr. Ken Beer from Summerside but Peach had already caught Joyce's baby girl. To wait out the storm, Dr. Beer crawled onto the couch beside the kitchen stove and had a catnap. Joyce recalls that Dr. Beer "was as a good old country doctor" and he often left Peach in charge of medicines and needles for various patients in the French River area.

Mary Liza Duggan was a midwife and a country nurse, also in French River. Her daughter Maisie was born in 1911. Maisie's husband ran was the lighthouse keeper in French River. When he died a few months later, Maisie Adams took over the lighthouse and became the first female lighthouse keeper in Canada, a job she had to fight to keep because she was a woman. She was making $16.00 a month and ran the lighthouse for 15 years.

Annie's daughter Maud born in 1905, told a story that occurred in December of 1917 after the Halifax explosion flattened half of the city. Annie Cody Henderson was a midwife. Her husband Cummings, a carpenter, went over to build houses in Halifax. Annie was left alone with ten children and a farm to run. One night, the family pig was about to give birth. Someone had to stand by to watch that the sow wouldn't roll over or try to eat her piglets, so Annie bundled up all the kids and they slept in the stalls with the cattle. The person who told this story said "the piglets all lived".

As famous as Lucy Maud Montgomery was, there was no one better loved in Lot 11 than Annie Cody Henderson.

Mary Jane MacKay (born in 1873) was also a midwife in Lot 11. She went to Prince Of Wales College with Lucy Maud Montgomery.

In those days many midwives lived on farms, had several children of their own, kept a herb garden usually of rosemary, thyme, sage and parsley, helped with planting, harvesting and milking cows.

Kathleen Henderson Jelly, at 93 years of age, told the story how she sympathized with her father that Annie was often away from home “midwifing” and might be gone for weeks at a time. When she was a school teacher she came home on weekends. She said one Friday she came home to find her mother had been away for days yet there were no dirty dishes, no sign of any cooking, no pots and pans, so she asked her father, "what did you have for dinner, Dad?" He said, "just put a couple of eggs in the teapot, and Kathleen asked, "...and for supper?" And he said, "well, I did the same again, just put a couple more in."

That weekend Kathleen baked him shortbread, biscuits and cakes. She found out later that they were all gone in two days and her father would be back boiling eggs in the teapot again.

Later, Kathleen gave up teaching and went back to school and became a registered nurse. Like most nurses at that time she received her training at the Infirmary in Charlottetown, originally the second PEI Hospital. It is now an apartment building located opposite the Charlottetown Civic Centre.

Kathleen nursed out in the country, only she was usually paid—unlike her mother Annie. After her dad died, Kathleen asked her mother, "how much did they pay you?" And Annie said, ”my dear child, I didn’t go to make money." Kathleen said that the doctor had told dad not to allow mum to go out anymore because her heart was too bad. But she went anyway, unable to say no.

In 1905, Jennie Maynard MacLean was born in Port Hill. Her midwife was a Mrs MacKinnon. Mrs MacKinnon would stay with Jennie's mum a few days before each of her children were born. Jennie remembers the day in 1915 when her youngest brother Courtney was born. That morning Jennie's mother and Mrs MacKinnon, the midwife, were banking the house with seaweed for the winter.

Jennie was told that the morning she was born in December 1905, her mother Annie killed a flock of geese, she plucked and cleaned them to sell for Christmas then went in and birthed Jennie. Jennie's father died in 1917, leaving her mother with five children to raise as well as a farm to run.

Mrs Hugh McKendrick was another midwife in the Port Hill area.

It is unclear if Mrs MacKinnon or Mrs McKendrick was the midwife for the birth of the "Port Hill Triplets" in the 1900-teens. The names of the triplets were Lorraine, Theresa and Donald Kilbride.

Maternity homes

There were three birth centres or maternity homes on the Island. They seemed to have been located in large farm homes of midwives. Interestingly, there was one in each of the three counties. The best known was Lettie MacKinnon's.

It seems that Lettie's maternity home of three beds was the best known of the three. Lettie was from Orwell Cove. She had been taking her nurse training at the Infirmary when her father became very ill and she went home to help out. She never finished her training but she was catching babies before she met and married Neil MacKinnon, a farmer from Earnscliff. They moved to Crossroads where they had a large dairy farm. She continued to catch babies and opened her maternity home in the large farm house.

Lettie was also very involved in helping on their large dairy farm while continuing to help out labouring women in their homes. She also boarded young single pregnant girls. She charged $7.00 a month and $3.00 a day after the birth. As if she didn't have enough to do, Lettie opened the telephone exchange in her home. She milked the cows morning and evening, gardened, and helped with the harvesting. She had several children of her own and sometimes kept the boarded girls' babies until the mothers — who were probably looking for work and housing — returned for the baby, or until the babies were ready to be taken to an orphanage. At one point, her house was inspected and she was forced to change her home to a boarding home.

Lettie kept careful records of her activities. Later her daughter-in-law, Queenie (Mutch) MacKinnon, who married into the family and also lived in the house, helped out with the boarding home, the telephone exchange, and the farm.

Queenie found out after Lettie's death that Lettie was the midwife who caught her. Dr. Herald Yoe said that if Lettie called him for help, he knew that her assessment of a birthing problem was accurate. She also worked with Dr. George Dewar who had his office in Bunbury, as well as doctors Pierce and Giddings in Charlottetown.

Betty Howatt mentioned a maternity home that was run by Mabel Sawler, a registered nurse from North Tryon. She was the daughter of Mabel Clark from Cape Travers who married a man named Sawler from Kentville. Mabel operated her maternity home before and after the Second World War. This maternity home was perhaps more like today's birth centres. She hired three midwives in North Tryon who provided care to pregnant women in the area. The three midwives were Mae MacKinnon Dawson, Sarah MacKenzie, and Flora MacThomas, all sisters of the same family. The maternity home was known as "Mabel Sawler's Birthhouse". They also worked with doctors in Summerside.

The third home of a midwife was up West in Foxley River. Less is recorded of this midwife's home, but Katheline Henderson Jelley said that her mother, Annie Henderson helped women deliver their babies in Foxley River, Murray Road, Conway, Popular Grove and Freeland, and some came up from Ellerslie-Bideford area to Freeland and stayed and she helped those mothers to birth their babies. There were probably more midwives who brought in labouring women who came to their door or were brought in and birthed their baby there with the help of a midwife. Perhaps not a formal maternity home.

In Lot 14, one of the midwives was Catherine MacLellan. Her daughter was Janie Pat MacLellan. Janie Pat saw, first hand, her mother going out through the snow banks to a birth ". Janie said, "if anybody wanted catting, Mama was there. That's the story!" Catherine MacLellan was a self-sufficient woman. When asked if her mother was a practical nurse, Janie Pat replied, "she was just a woman. She helped out everybody she could." When asked if her mother was paid, Janie Pat laughed and said "Paid?! She'd get that in heaven."